This post is not like my usual posts.

Over the last two weeks, I went on a Birthright trip to Israel. It was an uncharacteristically spiritual journey for me.

I was agnostic as a child. But this didn’t get in the way of my Jewish self-definition. Early on, I heard stories from my grandpa about his grandma’s execution by the Einsatzgruppen. In my ancestor’s deaths was a conviction for my own identity.

My group visited Yad Vashem a few days into the trip. I didn’t expect to learn anything new. I kept quiet. I braced for a heavy day.

Of all the exhibits there, one spoke to me most loudly. Maybe because it was in Russian. It was just a simple poem excerpt, describing a swamp called Babi Yar.

Над Бабьим Яром шелест диких трав.

Деревья смотрят грозно,

по-судейски.

Всё молча здесь кричит.

Translated,

Over Babi Yar wild grasses rustle.

Trees look sternly, as if in judgment.

Everything here screams silently.

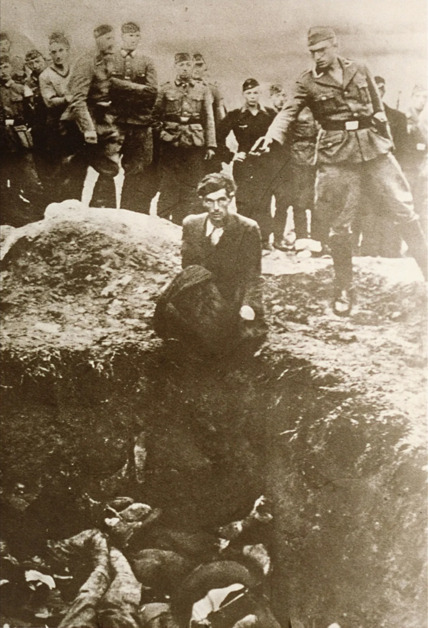

A picture of the valley echoes the poem, by Yevgeni Yevtushenko.

Here the entire Jewish population of Kiev was massacred; some whose names might never be known. Only their screams are captured silently in the grass which remains. With the current war it’s deeply saddening even the greenery has no rest.

Retelling my experience to my grandpa, he informed me that I had Ukrainian branches of family who were there, too. My grandmother told me their story. This was news to me. Yad Vashem curators make a point to separate the number 6 million piece by painful piece. With light editing, I present her words below.

My Great-Grandfather

By Alla Voloshina.

My maternal great-grandfather, Shenfeld David Solomonovich, was born in 1855 in a small Jewish village in Ukraine. These types of small Jewish villages in 19th-20th centuries were called mestechkos.

His parents were very poor and had a lot of children. He and his brother took turns to go to school in the winter because they had only one pair of boots for the two of them. Jewish people in Ukraine spoke a Hebrew-German dialect, Yiddish. When he was 12, David earned little bit of money by helping his next door neighbor, which he used to buy a Russian language textbook. He learned how to read and write from it. At 14, he left his family and his mestechko to look for better life.

His goal was to find a place where he could live and learn some craft, paying by his work for food and shelter. He was a tall, strong, and handsome young man, looking older than his age. His fluency extended to Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish. All of this helped him eventually be hired as an apprentice to a little vinegar production shop. Young David was fast learner. He could follow instructions for recipes and preparation methods to the tee. Gradually, he became an expert in vinegar production and a partner of the shop owner.

When the kinless owner retired, he left his shop to David. He was about 19 years old by then and already known in Ukraine as a vinegar production specialist. I don’t know anything more about how he expanded production or added some new products. I only know that he became a First Guild Merchant, which allowed him to live and to have property in Kiev (as there were restrictions where Jewish people were allowed to live in Russia). He married when he was 30, had two daughters Fania and Clara, and a son Peter, my future grandfather. When the Revolution of 1905 in Russia was brutally suppressed, his daughters were university students. They participated in student protests against police brutality and repression. The girls were arrested on multiple occasions. Each time their father would go to police, pay the Policmeister 100 rubles in silver, and take his daughters home.

His son Peter started to work at his father’s factory when he was still in Gymnasia (a selective private school in Russia before the revolution of 1917). It was expected that he would go to university to study organic chemistry, but he met my future grandmother, and decided that he wanted to get married. He was 18, and my grandmother was 16.

When I was a girl, I used to ask my grandmother why she agreed to get married so young. I still remember the smile on her face when she answered me: “Why would not I agree? He was very handsome, very rich, and very much in love with me. I was very happy to get married him.” They married in 1913. By that time both of my great-grandfather’s daughters were married, had one daughter each, and Fania had separated from her husband. Her husband was an opera singer, and a gambler. He lost his wife’s dowry to gambling and disappeared. In 1914, Russia entered World War One, and Fania became a front line military doctor. She lived a long life, was an accomplished doctor, but never married again.

My great-grandfather owned a two story house on the Obolonskaya Street in Kiev. His family, including my grandparents, lived on the second floor of that house. Family of the only hired worker of his factory resided on the first floor of the same house. The vinegar production factory was located next door.

Vinegar production is somewhat similar to wine production. The main production tools are some huge wooden barrels called chun, where the chemistry of converting input materials (grains or fruits) into vinegar take place. My great-grandfather, his son, and the hired worker took care of all production needs. The factory became very successful; it earned David Solomonovich respect as a merchant as product popularity grew. He earned enough money to provide for his family, paid his worker well, and invested extra money into real estate. He owned several apartment houses. The middle class folks, and artists, writers and actors rented apartments in his houses. The world-famous Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem lived in one of his apartments for several years. The script of The Fiddler on the Roof is based on the stories written by Sholom Aleichem. David Solomonovich used to tease his daughters on Friday evening after he had a glass of wine, saying that he is in the mood to go to Sholom Aleichem to talk about literature and art. Like all children, the girls were mortified with embarrassment, that their father would do such an awkward thing.

David Solomonovich considered these apartment houses to be a reliable and profitable investment. But the Great October Revolution of 1917 proved him to be wrong. Everything that he owned was nationalized. All personal valuables that he and his family had: gold and silver coins, watches, women’s jewelry and so on, were confiscated. The new authorities moved into his house several families of revolutionaries, leaving for my great-grandfather’s family two rooms in his own house. All capitalists, landlords, religious figures, and members of their families were denied the right to vote for 20 years.

Soon all aspects of life in the cities and villages of Russia fell to ruin. The bloody civil war lasted for more than five years. Famines in 1921-1923, and in 1932-1933, direct results of the Soviet ruling, lead to death of 12-13 million of Ukrainians.

Despite the cruelties of Soviet authorities, my great-grandfather did not lose his optimism. His faith, love of his family, talents, energy, wisdom and abilities helped him adjust to the new realities, and to continue his life as a decent, respected person, who was admired by his family, and by everyone who knew him.

Quickly enough, the new administration of his former vinegar factory realized that knowledge of Marxist theory did not help with vinegar production. My great-grandfather was invited to work at his former factory as a consultant, and my grandfather continued to do the manual work.

My mom was born in 1922. She cherished her grandfather’s memory, and I loved to listen her stories about him. She loved everything about him, but she was especially proud of his vast knowledge in theology, history, chemistry, and other sciences because everything he knew he learned by himself.

From 1930 to 1941, he traveled all over European part of Soviet Union to cure barrels of different vinegar production factories. His last business trip was in spring of year 1941, when he was 86 years old, just before Germany invaded Soviet Union.

Germany attacked the Soviet Union on June 22nd, 1941. Very soon my great-grandfather realized that Kiev will be occupied by the Germans. He insisted that his daughters and son with their families leave Kiev. However, he himself was not be able to leave because his wife was gravely ill from heart disease and could not travel.

Soviet authorities were organizing evacuation of important establishments, educational and scientific institution, hospitals, and factories. My mom, as a student, was supposed to be evacuated alone with Kiev State University, and only very last minute was she allowed to take her parents with her. My mom’s father, Peter Davidovich, was devastated, because he had to leave his parents behind. He had a weak heart, and he just died of grief four months after leaving Kiev, when he learned about the fate of his parents.

Within three months after the initial German attack on Soviet Union, on September 19, 1941, German forces entered Kiev, the capital of the Soviet Ukraine. On September 29-30, they murdered most of Jewish population of Kiev, over 33 thousand men, women and children at Babi Yar, a ravine northwest of the city.

This was how the life of my great-grandparents ended.

I am very proud to be descendant of the bright, talented, very kind and wise person, Shenfeld David Solomonovich, and I want my descendants to know about him.